Consider the file .bashrc. Normally, it’s permissions are set as thus:-rw-r--r-- 1 ghostdog ghostdog 913 Feb 12 07:55 .bashrc

Decoding this, means:

Owner can write (so our default user)

Everyone else can only read

So what would happen if we ran a malicious application that affects our bashrc file?

Consider the following simple C program:

1 |

|

Which writes the following to our bashrc (commends added for clarity):

1 | alias sudo='fakesudo' |

When the victim runs ANY command that involves the standard util sudo, it will now record their password to the file yourpassword.txt in the current working directory. If desired, you could clearly do much more than just simply write the password, like passing this root level access to your malicious executable. E.g:

1 | /bin/mymalware "--root-password=${pass}" |

or similar.

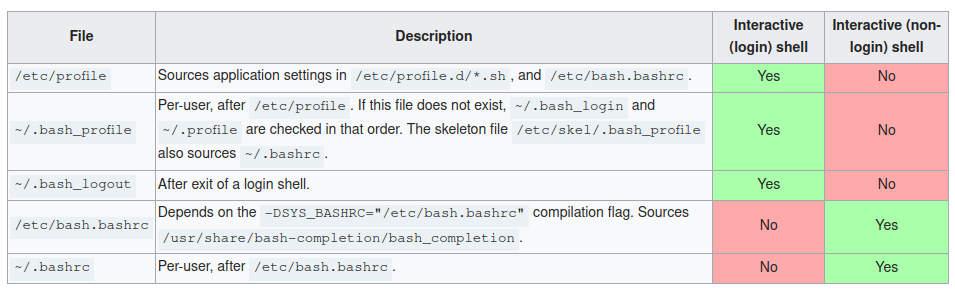

If we were being really nasty, we could even write the change to multiple bash startup files, as bash does not check the .bashrc file for non login shells.

Image credit: ArchWiki, Table colours added by user Alad on 16 Aug 2015, oldid=391339. Initial table also by Alad, oldid=335790.

This method of exploitation, as far as i am aware, has not been exploited, despite wide access to the bashrc file being common for default installations (it would be interesting to see if openbsd fixed this years ago, which I heavily suspect to be the case). And while users could just use \sudo every single time, I doubt anybody is doing that!

The advantage of this method, over something like replacing a binary, is that it is using expected and normal tools, thus it is very unlikely to trip an anti-virus or set off any red flags should someone hash their binaries to check them.

Mitigation of this is left as an exercise for the reader ;-)